Baseball Writers Ignore Their Own Rules. It Cost Pedro Martinez the MVP Award

As the author of a book about the most controversial MVP ballots of all time, I am often asked: “Which is the worst MVP vote ever?”

The answer really depends on how one defines “worst.”

- If on-field performance is the criteria, Washington Senators shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh in 1925 makes a case: The hobbled Senators shortstop appeared in 126 games, hitting .294/.367/.379 (generating 2.6 WAR). That he was named MVP over teammate Goose Goslin (.334/.394/.547/6.5 WAR) or Philadelphia’s Al Simmons (.387/.419/.599; 6.5 WAR) defies imagination. Peck’s reward for his MVP campaign? He was replaced at shortstop prior to the 1926 season.

- If production differential between the league’s best player and the player who was voted MVP is the criteria, then Mickey Cochrane’s 1934 selection might serve as a touchstone: Detroit’s Cochrane (4.5 WAR) was worth 6 wins less than Lou Gehrig, whose .363/.465/.706 Triple Crown effort rated 10.4 WAR.

- If (alleged) voter spite is the measuring stick, the 1947 ballot slithers to the top of the list. In the closest vote in MVP history, Ted Williams lost the award to Joe DiMaggio by a single point (202–201). Despite slugging his way to the Triple Crown and leading the league in essentially every meaningful offensive category save stolen bases, Williams was left off the ballot of one anonymous voter. Williams assumed for decades that it was one of the Boston writers with whom he had long sparred, but this was never proven.

- If it’s the inexplicable selection of an unqualified player over a slew of seemingly superior candidates, then Juan Gonzalez in 1996 might be your cup of tea. As ranked by WAR, Gonzalez (3.8) wasn’t one of the fifteen best players in the league (while runner-up Alex Rodriguez was arguably the best player in the league).

But if you rank your terrible MVP selections based on the level of dishonesty, hypocrisy, or bureaucratic incompetence attendant to a vote, there is only one choice for the worst MVP vote of all time.

“What game were those guys watching?”

By now, you doubtlessly know part of the story: In a tight vote, Texas Rangers catcher Ivan Rodriguez was named 1999 AL MVP over Pedro Martinez. Boston’s otherworldly right-hander captured more first-place votes than Rodriguez, but was famously left off two ballots — omissions that cost him the award.

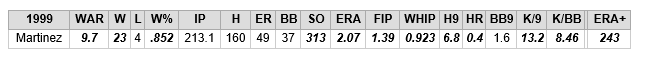

It’s a slight Martinez carries with him like a post-career limp, and you can’t blame him. Despite pitching into the teeth of a violent offensive storm (AL teams averaged 5.18 runs per game, 12th highest in history), Martinez produced one of the great pitching lines of the last 100 years.

Martinez earned the elusive “Triple Crown” for pitchers, leading the league in wins, ERA, and strikeouts — but that barely begins to capture his achievement. As measured by WAR, he was 50% better than the next best pitcher in the league; his ERA was more than a full run better than the next best in the league; and despite missing four starts to injury, he struck out 313 batters in season where only one other pitcher reached 200. His fielding-independent pitching (FIP), which strips team defense from the equation when measuring pitcher effectiveness by comparing HR/9, K/9 and BB/9 rates to the league average, is the lowest ever recorded (1.39). His adjusted ERA (243 ERA+), which compares a pitcher’s earned run average to the league average while adjusting for where he pitched, is one of the 10 best ever recorded — and was almost twice as good as the runner-up in that category for 1999. His 0.92 WHIP is excellent, but not historic — until one realizes it was 33% better than the next pitcher on the leaderboard. His 13.2 K/9 basically lapped the next-best in this category (8.4 K/9), and he was able to deploy this power with remarkable precision: Martinez struck out 8.5 men for every man he walked.

For good measure, Martinez also pitched his team into the playoffs: Boston’s record in games started by Pedro El Grande was 24–5; it was 70–63 in all others. For equivalency in dominance relative to the league, one has to look to Babe Ruth in his prime. [1]

None of this is to suggest that Pudge Rodriguez didn’t deserve some consideration for the MVP award (especially if you value the often underappreciated defensive responsibilities of catcher). If, as a catcher, you hit .332/.356/.558/125 OPS+ while playing indisputably great defense for a playoff team, you’re going to get your share of votes. And you should get your share of votes. Pudge Rodriguez had a fine year, and deserved to place among the top-five on the ballot. In many other years, Rodriguez might have been a sound choice for MVP.[2]

But 1999 wasn’t like many other years — not when Pedro took the mound. Despite pitching in one of the toughest environments ever for pitchers, the dynamic star produced a season out of the Dead Ball era. Yet two writers — George King of the New York Post and La Velle E. Neal III of the Minneapolis Star Tribune — failed to list the amazing Martinez on their ballot.

Said Ted Williams of this ghastly omission: “What game were those guys watching?”

Of the two snubs, the King “non-vote” was, at first blush, the more infuriating. Despite listing pitchers David Wells and Rick Helling (he of a 4.41 ERA) on his ballot the year prior, King defended his treatment of Martinez by saying the “MVP is for everyday players. Pitchers have their own award.”

That King, a year after voting for two pitchers, would claim the “MVP is for everyday players” was laughable. His snub of Martinez was so bad that his own newspaper called it “bunch of hogwash.”

King’s hypocrisy was galling, but it’s not what makes 1999 so notable. It’s La Velle Neal’s snub of Martinez that differentiates this terrible MVP ballot from the dozens of questionable votes that have marked the award’s history.

Because La Velle Neal should not have been allowed to vote in 1999.

“Anybody that cannot vote for a pitcher, we replace them.”

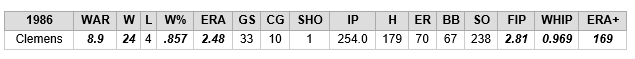

The numbers were there. If one were making a case for Don Mattingly as the American League’s Most Valuable Player for 1986, the numbers were there:

And then there was the crouch, the slightly busy feet in the box (always tinkering), the compact blur of a swing. The eye black. The moustache. Fathers to sons: “That’s what a ballplayer looks like.” Style points count.

That Mattingly was going to capture his second consecutive MVP award was a foregone conclusion, a way to reclaim the headlines from the cross-town Mets (still reveling in World Series glory), and a small measure of consolation for the Yankees’ disappointing second-place finish.

The voters had other ideas:

“Roger Clemens, who won his first 14 decisions this season and wound up with a 24–4 record in leading the Boston Red Sox to their division title, capped his dream year yesterday by being voted the league’s Most Valuable Player Award.”

— Associated Press, November 19, 1986

The news hit the sensibilities of Yankees fans with the impact of a Clemens four-seamer to the ribs. The Boston ace took the award with room to spare (19 first-place votes to five), and the indignation of New York fandom was enflamed. The Clemens vote was an outrage splashed in 40-point type across the back pages of every tabloid in the city.

Adding fuel to a roiling hot-stove debate, Hank Aaron called the pick “a joke.” Ron Darling, starting pitcher for the champion Mets, was flabbergasted: “It’s hard for me to think how Mattingly could have lost the award. I’m one who believes everyday players should win.” NL MVP Mike Schmidt was more diplomatic, but commiserated with Mattingly: “(Clemens) may be an exception, he was so dominant. But I’m not in favor of a pitcher being considered for the MVP.”

Not everybody agreed that Mattingly was robbed. Hall of Fame right-hander (and 1968 NL MVP) Bob Gibson scoffed at the notion that a pitcher can’t be as valuable as an everyday player: “You can tell what I count for as a pitcher every time I go out there.” Boston Manager John McNamara, who understood Clemens’ value more than anybody, said: “There… [is] only one Roger Clemens.”

Ultimately, Jack Lang, secretary-treasurer of the Baseball Writers Association of America, quelled the debate by offering a stern rebuke to those who would suggest a pitcher should never win the award: “The rules that are sent out to the voters on the [MVP] committee state: ‘Keep in mind that all players are eligible. That includes pitchers.’ Anybody that cannot vote for a pitcher, we replace them. In my 22 years running elections, only two writers have said that to me.”

“I was ripped apart.”

In the aftermath of the 1999 vote, La Velle Neal was pilloried in the media. Unlike George King, he met the withering criticism with a reasoned defense of his ballot. “I just feel that in order to be an MVP you have to be in the battle every day,” said Neal. “If I believe a pitcher should not be in the running, why would I put him on the ballot at all?”

The logic is sound. If you’re being intellectually honest, you wouldn’t concede even a 10th-place vote to a pitcher if you believe pitchers aren’t eligible for the award. But striking pitchers from consideration violates not just the spirit of the voting rules, but the letter of the voting rules. It’s why, in the words of Jack Lang, the BBWAA disallows anybody who holds this position from voting.

Why, then, did Neal have a vote in 1999?

Did he neglect to inform the BBWAA of his stance on pitchers and the MVP? Did the BBWAA have knowledge of Neal’s anti-pitcher position, but choose to send him a ballot anyway? Did the rules regarding voter eligibility change since Roger Clemens took the award 13 seasons prior? (Note: I contacted the BBWAA clarification on their voting policies; request for comment went unanswered).

Only Lang (who passed away in 2007) and Neal know the answers to these questions. What’s left is the fact that Pedro Martinez was cheated out of his rightful MVP by a procedural snafu, a miscommunication between the BBWAA and one of its members, or intentional deception on the part of a voter. According to the BBWAA’s own rules, La Velle Neal should not have had a vote in 1999; had the ballot gone to another writer per BBWAA policy, Martinez may very well have notched the additional first-place vote he needed to secure the award (as it was, he garnered more first-place votes than any other player, despite being left off two ballots).

The sting of the 1999 vote hasn’t abated for Martinez. “I was ripped apart,” he said in 2012. “I’m not afraid to say that the way that George King and Mr. LaVelle Neal III went about it was unprofessional.” Three years later, in his 2015 autobiography, Martinez openly wondered if racial bias played a part in the MVP vote.

This wasn’t the last MVP controversy generated by Neal. Despite being on record that he won’t support a pitcher for MVP, Neal was again given a vote in 2012. Days before the ballots were due, Neal published a column with the headline “Angels’ Trout is the Right Pick for AL MVP.”

It was later revealed that Neal gave his first-place vote to Miguel Cabrera.

Neal was elected president of the BBWAA in 2013.

Jeremy Lehrman is the author of Baseball’s Most Baffling MVP Ballots. For more baseball, click here.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

- Or one can look to Martinez the very next season: He was even better in 2000 than in 1999. On an adjusted basis, his 1.74 ERA in 2000 is the lowest ever recorded (291 ERA+). He was a non-factor in the MVP vote.

- Well… maybe. While his batting line is eye-popping for a catcher, we should remember the context: Rodriguez played in one of the game’s best hitter’s parks during one of the game’s best seasons for offense. His 125 OPS+ ranked 24th in the league; as ranked by WAR, Rodriguez (6.4) was the seventh-best player in the league.